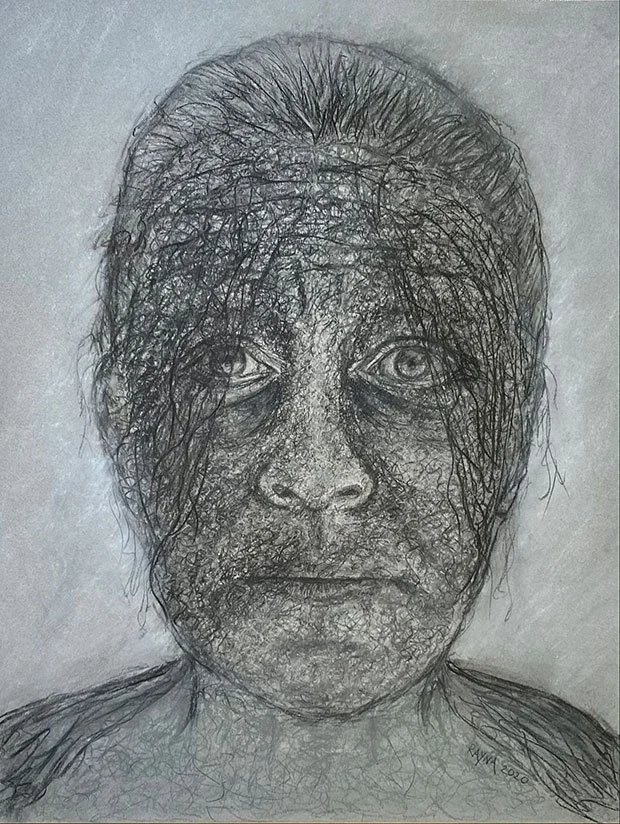

RAYNA VAUGHT GODFREY, PhD

Charcoal sketching is messy. Smudges and smears everywhere, there is no clear-cut path as you work with crumbling pieces of burnt vines and willow branches to render the unknown into some sort of meaning.

Creating with charcoal is a study in impermanence. Images easily disappear with the purposeful swipe of a chamois cloth, the inadvertent bump of a shirt sleeve, or the brush of a trailing wrist. It is an exercise in awareness and presence, in patience and perseverance. The work never feels completely finished. It’s an ever-evolving process, seeming like there is always one more mark to adjust, a shadow to move, a value to shift. At some point, you take a peaceful breath and say, “good enough.”

As a psychologist specializing in grief and loss, I have been present with powerful and overwhelming grief from all manner of illness and accident and treachery; from endings contemplated and random, welcomed and protested. Like charcoal, grieving is messy. It is not linear or stage-like in progression. Grief swirls around and spirals off, circling back on itself again and again. Like charcoal sketching, grief therapy sets out to render the unknown into some sort of knowing, to make some kind of meaning of the impermanence. You help the client adjust boundaries, explore shadows, shift to a new sense of self. At some point, you take a peaceful breath and say, “good enough.”

Grief

(Charcoal on Paper, 19” x 25”)

This sketch is an impermanent glimpse of grief’s messy process. As with therapy, you have to explore the swirls and spirals to find your meaning. And as with grieving, everyone’s meaning will be different. Perhaps the gaze offers the suggestion of sadness and exhaustion, or hints at despair. The set jaw might indicate strength and resolve, with lips poised for hope. The eyes warn you to step back, or they implore you to move closer and hear her story; to connect with her in her pain and maybe share yours too.